(Net-native storytelling and the tactics of sharing power with an audience. Written in 2006, but still relevant, I think…)

The Beast

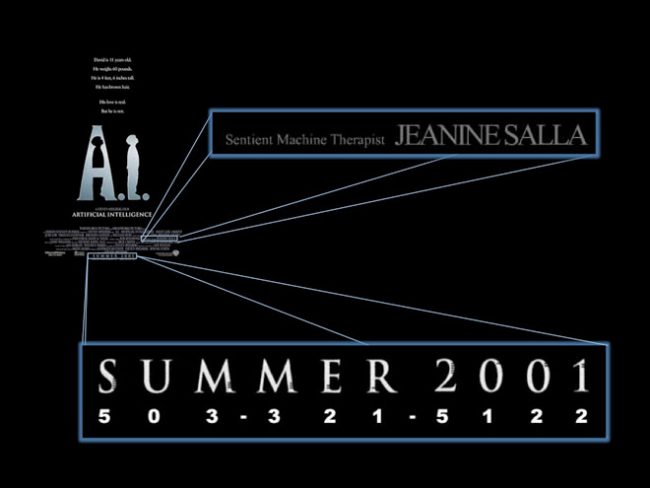

At the beginning of 2001, visionary genius and all-around nice guy Jordan Weisman invited me to be the lead writer on a project designed to generate interest in the world of the upcoming Steven Spielberg movie, AI. I didn’t know it at the time, but I had just fluked into the chance of a lifetime – to get in on the ground floor of what might be the signature art form of the 21st century.

Jordan’s idea was that we would tell a story that was not bound by communication platform: it would come at you over the web, by email, via fax and phone and billboard and TV and newspaper, SMS and skywriting and smoke signals too if we could figure out how. The story would be fundamentally interactive, made of little bits that players, like detectives or archaeologists, would discover and fit together. We would use political pamphlets, business brochures, answering phone messages, surveillance camera video, stolen diary pages…

…in short, instead of telling a story, we would present the evidence of that story, and let the players tell it to themselves.

The very first asset list ever compiled for the game contained 666 items, so we nicknamed it The Beast. The nickname stuck, and has become, for better or worse, more appropriate with the passage of time.

Slouching Toward Redmond To Be Born

Every communication platform can (and eventually will) create an art form. The novel is part of what the printing press means; the countdown to Citizen Kane began as soon as the first motion picture camera was invented.

Here is my very large claim: however shambling, ungainly, and awkward it will come to seem in retrospect, The Beast was the first truly successful prototype of what web-based story-telling wants to be.

The world of the info sphere – the web and google and email and instant messenger and cell phones – is about two fundamental activities: searching for things, and gossiping. Jordan’s genius was to recognize that, and build a storytelling method to match.

In the years since the Beast ran in the spring and summer of 2001, the audience for this kind of story-telling has given it a name: ARGs, short for Alternate Reality Games.

I have been lucky enough to work with Jordan and Elan (and many other truly talented people) on the two largest ARG’s created by the end of 2004, The Beast and I Love Bees. I cautiously offer a few thoughts on ARG’s in general, as well as the projects I have worked on.

What is an ARG?

Building an ARG is like running a role-playing game in your kitchen for 2 million of your closest friends. Like a role-playing game, we get players to actually enter the world of our story and interact with it, both online and in the real world.

The Beast was an online story told in a world a thousand web pages deep, where players discovered the plot and interacted with characters over phone, fax, email and website.

For I Love Bees, players decoded GPS locations and raced all over the United States to piece together more than 5 hours of radio drama being broadcast in 45 second snippets over payphones.

(Yes, that’s right. I am asserting that a key moment in the development of 21st century art had to do with the broadcast of a 1930’s style radio show – about a 26th century alien invasion – over an all-but-obsolete tech platform. The future is never quite what you expect.)

For me at this time, the hallmarks of an ARG are:

- A story which is broken into pieces which the audience must find and assemble

- The story is not bound by medium or platform: we use text, video, audio, flash, print ads, billboards, phone calls, and email to deliver parts of the plot.

- This audience is massive and COLLECTIVE: it takes advantage of communication tech to work together

- The audience is not only bought into the world because THEY are the ones responsible for exploring it, the audience also meaningfully affects how the story progresses. It is built in a way that allows players to have a key role in creating the fiction.

Broken Into Pieces

In the Beast, the story was hidden across scores of websites and real world communications. On ILB, we took nearly 6 hours of radio and broadcast it in 45 second chunks over payphones identified only by GPS locations.

Why?

Because treasure hunts are fun. Because a story an audience assembles is one in which they have far greater investment.

Because looking for stuff and gossiping about it is what the internet means.

Platform Independent Story Delivery and What “Pervasive Gaming” Means

You can read a book about Harry Potter or Narnia. An ARG allows THE PLAYER HIMSELF to walk through the back of the wardrobe, and find Narnia in the real world, and use the skills, abilities, and friendship he possesses in the real world to influence what happens to Narnia.

Or, more exactly, it allows Narnia to come to him.

Put another way: An ARG doesn’t happen between the covers of a book, inside the walls of a cinema, or framed by a computer console. An ARG comes at you over the many channels you use to receive and communicate the facts of your daily life.

I once jokingly said that if Moby Dick was an ARG,

- you’d see a whale swim by outside your window,

- Ahab would call you on the phone, and

- a harpoon would come flying out of your television set.

What “Platform Independent” means for the audience

This experience, which leading scholar of the form (and pal) Jane McGonigal calls “pervasive gaming,” has some interesting consequences. Because the next time your phone rings it might be Ahab on the line, we ask you, the player, to allow a soap-film thin bubble of suspension of disbelief to follow you around during your daily routine. Players and creators invest a lot of trust and energy in not popping that bubble.

One player summed up the typical player mode brilliantly by saying, “It’s like a role-playing game where you play a character who’s exactly like you, only she believes it’s real.”

This Is Not A Game

One of our key slogans for the Beast was, This is Not a Game. We wanted to write characters that were more like people than the characters in video games. We wanted the phone numbers in the game to work like real phone numbers; the emails to feel like real emails; the websites to present as real websites. This fetish for verity has real costs and consequences, and nobody has chafed under the restrictions more than us.

Obviously, the archaeological model – that players are piecing together a story from real elements – seemed to work better when the pieces were realistic. But the drive for This Is Not A Game was more intense than that, driven particularly by Elan’s instincts.

I have a very healthy respect for Elan’s instincts; in my opinion they have been the single most important factor in bringing Jordan’s vision of this art form to the world -more key, though I hate to admit it, than the writing. (And Elan makes me do 5 and 10 and sometimes 20 drafts of what I write, so that’s subordinate to his vision as well!)

With the benefit of hindsight, I think our compulsive desire to stick by the credo of This is Not a Game had to do with Elan’s understanding of the fragility of that soap-bubble of disbelief. When you ask someone to pretend to believe in an experience that could engage them at any time over any channel in their ordinary lives, you have to make it as easy as possible for them to suspend their disbelief.

For both the Beast and I Love Bees, we refused to do interviews under our own names until very near the end. It’s OK to see the name of a book’s author on the cover – but imagine how jarring it would be if periodically the actual narrative of your Napoleonic era sea story was interrupted by someone reminding you it had been written by a little old lady named Doris who lived in a condo in Tampa and liked Siamese cats.

When there is no frame around a story, you have to be really careful about reminding the audience that it is, after all, “just” a story…

What “Platform Independent” means for the developer/author

When we talk about “computer games,” what we are usually referring to are console-based video games, which use computer-generated graphics to immerse a player in an imaginary experience (e.g., you play a figure on the screen who has to shoot a lot of bad guys before he gets shot).

But console games, you could argue, are horseless carriages: they are a hybrid of computer chips and TV. The idea behind video games comes from an era before the web, and indeed before the internet was anything but a message system for university researchers. Video games also really gained momentum during the age in which “virtual reality” was the future we thought computers were taking us too, as opposed to, oh, “distributed reality” or something that seems more accurately to model Where We Are Now and where we seem to be headed.

Console games have historically been driven by the urge to create more convincing graphics–to create virtual realities. This involves spending enormous amounts of time, money, and ingenuity developing realistic-looking physics (to govern the relationships between objects in the virtual world) and graphics (to make those objects look satisfyingly real.

ARG’s step sideways around that whole question by using:

- reality, where the physics and graphics engines are

- perfect, and

- won’t change between development and delivery, in conjunction with…

- the infinite resolution renderer — a.k.a. the human imagination.

Mantra: Story, Not Platform

The ARG cares about the STORY, not the platform. ARGs carry on the impetus of film, and opera before it, by gathering and deploying any other artistic resource�music, costume, drama, lighting, graphics, games, clowns on unicycles with their hair on fire�to deliver the story. In fact, one of our alternate names for ARGs is “search operas.”

Massive and Collective Audience

At heart, I am (narrowly) a novelist, and (more broadly) an entertainer. Considering ARG’s from the point of view of a practicing artist, it seems to me that their weirdest attribute is the nature of the audience.

Reading a book is a private activity. Watching a movie is another private experience. You may have it in a theater full of other people, and that may color your experience, but essentially the work of art is delivered to you privately.

Because ARG’s have to be assembled by large communities of people, they create a “collective” audience. You could, of course, construct a single-player treasure hunt, but I think most ARG players would feel you had missed the point. The act of the audience finding the story, guessing at its meaning, and co-constructing the narrative is fundamental to the art form. A set list from Woodstock does not tell you what Woodstock meant. (In fact, one player of the Beast who was also at Woodstock said that it and the Beast shared an electric sense of the communal discovery of a new world that he had never experienced anywhere else.)

This sense that the reality is something everyone is discovering together is, I think, another thing that the web means.

At the risk of digressing…

I grew up mostly in Canada. In a Canadian winter, there is a sharp distinction between the Interior (private, personal) space of your home, and the Exterior (public) space outside your front door.

Now that I live in California, I spend a lot of time between those two places, in what you might call Patio Space, or, in the South, Front Porch space. The front porch is personal, but public – you can see the people on the street, and they can talk to you. Perhaps they will come in and sit a spell.

The contemporary web-based culture of blogs and livejournals exists in Front Porch space to a degree utterly unlike the world I grew up in. It seems to me that ARGs exist there too – in the personal-but-shared space of IRC channels and community sites. The front porch and the irc channel exist for the mingling of work and gossip. The ARG reflects and embraces a culture that is leveraging the possibilities of the internet (and the cell phone) as a social platform.

The Grand-Daddy of all ARG’s

By the way, I do NOT assert that the Beast was the first, or greatest, example of massively multi-player collaborative investigation and problem solving. Science, as a social activity promoted by the Royal Society of Newton’s day and persisting to this moment, has a long head start and a damn fine track record. Not to mention more profound investigations and way more scandalous gossip.

We just accidentally re-invented Science as pop culture entertainment.

Interactivity

One of the things that feels most exciting to players of ARG’s is that they get to co-create them. It’s fun to reassemble a story – but even more of a power trip to actually change it.

William Gibson, once asked to comment on the wildly exciting possibilities of hypertext, guardedly replied, “Well, as a writer, I like to put words in a certain order, and I kind of hope they stay that way.”

If there is any skill at all involved in telling stories (and my vanity wants to believe there is) how do we reconcile that with the ARG audience’s profound desire to affect the narrative? If the game is real, then what they do should really change it, right?

In general, I would say there are three basic strategies to interactivity in ARGs:

- Power without control: Give players power over the narrative in carefully defined situations,

- Voodoo: allow players to contribute the “raw material” out of which you fashion story components.

- Jazz: Build the game with enough blank spaces written into it, and a commitment of time and resources to let yourself take directions from what the players do.

Really, this is just like GMing a role-playing game, right? You set an objective, you have certain story elements you’re going to hit, but within those broad boundaries, the fun is in letting the players create their own adventures.

Yeah, but what does that mean, really? (With examples)

Give up power but not control. E.g. Players get the password to unlock an online diary. Formally, they have to perform a set task to trigger the delivery of the next bit of story, granting them “power” without “control.”

In the Beast, we intentionally left a hole whereby a player could “hack into” one of our websites, altering something in the world. (In this case, the names of people ostensibly in a morgue.) It was our hope that one of the players would “hack” the site and insert a Name X into the list, after which characters in our world would say, “Oh no! X is dead!”

A player named Campfly did exactly this (and to our relief did not scribble obscenities into the site. To preserve the feeling of reality, we let him write whatever he wanted to, and graciously he elected not to make us have to censor him.)

This kind of interactivity is controlled, but I would assert, also feels very real to the player who gets to palpably change the fictional world. It’s true that we were going to get from Point A in the story to Point B: but if the players get to choose the route between A & B, AND drive the car, surely that isn’t just illusory interactivity.

A subset here is closed tree branching. At certain points in a story, you can allow for multiple outcomes, and let the players determine which is correct. Famously, the vote on AI rights at the end of the Beast was completely unrigged, and we shot two different ending videos to release depending on the direction the players took.

Obviously this has to be used very conservatively. Nobody has the resources, in time or money, to create a lot of material which never gets seen.

Voodoo

Just as a voodoo priest might make a magic doll out of someone’s fingernails and hair-clippings, the creators of an ARG can solicit (or just co-opt) material from players and incorporate it into the game. We have invited player submissions directly into our worlds – for example, the Metropolitan Living Homes Architecture contest, where we took player-designed in-world houses and set them up for display.

Or, in I Love Bees, we had a character named the Sleeping Princess, who needed players to help her learn to speak. For a whole week, this character could only speak in words and phrases taken from player emails to her. The nightmare database we turned into Loki’s dying soliloquy in The Beast would be another example of allowing players to supply the raw materials out of which you will build parts of your story.

Jazz

Players and PMs (puppetmasters) have a certain call-and-response, jazz-style interaction. The upside of this is that it increases the ownership of the players in the game enormously. The down side is that

- you have to have a story defined loosely enough that it can accept huge changes in the predicted content, and

- you have to commit to producing this stuff on the fly and very nearly in real time. That puts some constraints on the kind of material you can make, but you can do a lot. It just, you know, costs you unbearably in blood sweat and tears over any extended period of time.

The easiest example of this, again from the Beast, is the character of the Red King. Originally we wrote a site that had been hacked and tagged with the single line “hackd & crakd by Red King.” Our web developers put that line in a sound file loop instead of just writing it, and players were instantly FASCINATED by this Red King guy, who was never more than a line of graffiti in our heads. But we threw up our hands and starting writing about him, more and more, until he eventually became one of the three principle characters in the game.

The Step-Self story in The Beast was driven by players finding we had slipped up and used the same piece of stock art twice. In I Love Bees, the Operator’s missions for her crew were driven by trying to imagine ever more challenging uses for the communications infrastructure the players themselves had built.

[fbcomments]